Sam Cooke left Keen Records after three years to join RCA in January 1960. The obvious attraction was the opportunities offered by a big multi-national against those on offer at Keen, a small independent label. He would now be working with producers Hugo and Luigi and would be recording in top-class studios. He had also been offered an advance of one hundred thousand dollars, which equates to around one million today!

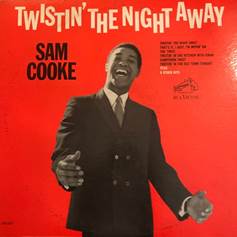

During 1960 and 1961, Cooke recorded four studio albums at the RCA Studios in New York City, but in December 1961, he switched to RCA’s studio in Los Angeles to complete his fifth RCA album “Twistin’ the Night Away”. The first track had been completed in January 1961 in New York; after a break of almost a year, and then the rest of the album was recorded on December 18th and 19th, 1961 and on 15th, 16th and 19th February, 1962, in Los Angeles. The album was released the following April. Cooke recorded three more studio albums in Los Angeles at the RCA Studio in Hollywood, which were released in 1963 and 1964.

“Twistin’ the Night Away” offers twelve tracks, of which Sam Cooke wrote seven (one with Lou Rawls). Sammy Lowe, who had conducted the previous two albums in New York, arranged and conducted just one song on the new album, “That’s It – I Quit – I’m Movin’ On”, which was released as a single on February 14th, 1961. The remaining eleven tracks were arranged and conducted in Los Angeles by René Hall, who had also worked at Keen. Hall brought in three Los Angeles saxophone players to get the sound he wanted: Jackie Kelso and Plas Johnson on tenor sax and Jewell Grant on baritone sax. Several other members of the Wrecking Crew were on the sessions in Los Angeles, including Clifton White and Tommy Tedesco, who shared guitar duties with René Hall, Red Callender (bass), Earl Palmer (drums), Eddie Beal (piano), Stuart Williamson (trumpet) and John Ewing (trombone). A string section of seven violinists added to the fun.

The album is essentially a reason for dancing the Twist, with five of the songs featuring twisting or twist in the title. The songs are mostly up-tempo, with punchy saxophones and sing-along choruses that are probably intentionally repetitive. The stand-out track is “Somebody Have Mercy”, the only Sam Cooke composition included in the collection. It is slower, with a Gospel-tinged arrangement that shows off Cooke’s voice to great effect.

The album, Cooke’s eighth, entered the Billboard Top LPs Chart but only rose to number seventy-four. Nevertheless, it was the first of his albums to enter the chart since the initial Keen album “Sam Cooke” in 1958. Two of the three singles drawn from the album did a little better. “That’s It – I Quit – I’m Movin’ On” was issued well in advance of the album’s release and reached number thirty-one on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles Chart and number twenty-five on the Billboard R&B Singles Chart. “Twistin’ the Night Away” improved on that, when it was released on 9th January 1962, climbing to number nine and number one on the respective charts. It also peaked at number six on the Official UK Singles Chart. Regular sales in subsequent years finally earned Cooke a silver disc from the BPI on the 2nd August 2024, over sixty years after its original release! What an amazing achievement, demonstrating Cooke’s legendary status and appeal to later generations of music fans. The third single released, “Twistin’ in the Kitchen with Dinah”, failed to chart.

The second Sam Cooke studio album to be recorded in the RCA Hollywood studio was “Mr Soul”, his ninth overall, with recording starting on 23rd August and continuing on 29th November and finally on 14th to 16th December, 1962. The completed album was released by RCA Records in February 1963. The album offers a masterful blend of older Rhythm and Blues, Soul, and Pop standards, completely different from the previous album “Twistin’ the Night Away”, and showcases Cooke’s versatility as an artist. The album contains twelve tracks written from the thirties to the late fifties, plus just one from Cooke this time.

It is interesting to speculate why these songs were chosen, given that many of them are associated with world-famous singers from previous generations who covered a range of styles and genres. It may be that the songs chosen for this album were simply some of Cooke’s favourites and he wanted to put his own spin on them. It is also possible that he chose them as a tribute to some of his favourite singers, from whom he had learned a lot.

There are four songs on the album written during the thirties. The earliest is track eleven, “Little Girl”, co-written by Francis Henry and Madeline Hyde, which was recorded by Sam Lanin & His Orchestra in 1931. The second is “Willow Weep For Me”, written by Ann Ronell in 1932, which was originally recorded by Paul Whiteman & His Orchestra with Irene Taylor and has since become a standard. Versions that Sam Cooke must have heard include recordings by Billie Holliday, Sarah Vaughan, and Frank Sinatra. Other artists from Cooke’s generation also covered the song, the best-known of which are Nina Simone (1959), the Coasters (1960) and Lou Rawls (1962). The third of the four oldest songs is “Smoke Rings”, composed by H. Eugene Gifford (music) and Ned Washington (words) and recorded by the Casa Loma Orchestra for Brunswick in 1932. The last of the four is the album’s closing track, “These Foolish Things (Remind Me Of You)”, written by Harry Link, Holt Marvell and Jack Strachey for a late-evening revue on the BBC in the UK in 1936. It was recorded by Nat King Cole in 1957. Sam Cooke respects the swing of the originals but adds a touch of Soul.

From the forties, Cooke chose three more songs. “I Wish You Love”, co-written by Charles Trenet and Albert Breach in 1942, “Driftin’ Blues” written by Charles Brown, Eddie Williams and Johnny Moore in 1945, and “For Sentimental Reasons” co-written by Deek Watson and William Best also in 1945. This last song was one of Nat King Cole’s biggest hits on its 1946 release!

“I Wish You Love” was also covered by Nat King Cole, along with over a hundred other singers. Sam Cooke’s version is interpreted in a smooth, sophisticated Pop-Jazz ballad style, with strong influences from traditional Pop and Supper-Club crooning made popular by artists such as Nat King Cole or Frank Sinatra. The vocal style of Cooke’s delivery is restrained and elegant, showing off his smooth phrasing and emotional subtlety, rather than the raw Gospel-Soul power he’s known for on other songs. The arrangement of this particular track features lush orchestration with strings and soft Jazz instrumentation — think soft piano, brushed drums, subtle horns. The tempo is slow and the mood is romantic, conveying bittersweet emotions with a gentle, sentimental feeling.

The second, “Driftin’ Blues”, is in many ways an odd one out on the album. It was written in Los Angeles in 1945. The three co-writers were members of the trio Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers, who recorded the song for Philo Records in 1945 (Philo soon became Aladdin, of course), with Charles Brown playing piano and singing lead on the track. Brown was still in high school at the time; it was the first of his songs that he had recorded. It sold well in Los Angeles and beyond, and has become a Blues classic. Sam Cooke was fourteen years old when it was released, so he probably heard it a lot!

Four more songs for the album were chosen from the fifties. They are “Chains of Love” (1951), written by Blues singer Doc Pomus, “Cry Me A River” (1953), composed by Arthur Hamilton, “All The Way” (1957), co-written by Jimmy Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn, and finally “Send Me Some Lovin’” (1957), penned by John Marascalco and Leo Price.

Doc Pomus sold “Chains of Love” to Ahmet Ertegun, who thereby acquired the song’s copyrights too, so it is the latter’s name that appears with a writing credit on Big Joe Turner’s original version of the song in 1951 on Atlantic Records. The single reached number two on the Billboard R&B Singles Chart, so Sam Cooke would have known it well. “Cry Me A River” was a big hit for Julie London in 1955, and Frank Sinatra took “All The Way” into the charts in 1957. Sam Cooke’s versions of these songs are all sung with his distinctive Soul-tinged vocal smoothness. He does justice to them all.

The last of this set of four, “Send Me Some Lovin’”, is another odd one out. It was recorded by Little Richard in 1956 in New Orleans and released by producer Art Rupe on his Specialty label in 1957. Little Richard’s version is surprisingly slow and heartfelt but has its roots in R&B and early Rock & Roll. Cooke reinterprets it through his own distinctive lens, giving it a more refined Soul treatment. His version leans into Soul but retains the song’s R&B structure, with gentle Doo-Wop-style backing vocals that echo and respond to his lead — a style that was a staple in early Soul and Pop ballads. With a more laid-back groove than Little Richard’s grittier, piano-driven original, the arrangement is softer and more romantic, with a relaxed rhythm section, light piano, and subtle horn touches. It’s less about urgency and more about longing. The vocal style has Cooke’s typical smoothness and emotional restraint, focusing on conveying yearning and vulnerability rather than raw power. He turns a straightforward plea into something intimate and aching. The production is slick, again typical of his RCA period, with clean, polished studio work. The strings may be understated, but there’s a definite richness to the sound.

In summary, “Send Me Some Lovin’” is classic Sam Cooke — romantic, polished, and emotionally sincere. He transforms a raw R&B classic into a tender, almost crooner-like Soul ballad, perfect for slow dancing or wistful reminiscing. It bridges the gap between the raw energy of 50s R&B and the smoother, more emotive Soul of the early 60s.

That leaves the one Sam Cooke composition on the album, “Nothing Can Change This Love”. It was released as a single on 11th September 1962. René Hall’s arrangement is a masterclass in subtlety and elegance. The introduction showcases the exceptional talents of Earl Palmer, Edward Beal, and René Hall, the members of the rhythm section, who each contribute their unique artistry to create a warm and inviting opening. Palmer’s drumming in the intro is understated yet striking. His use of a gentle backbeat provides a steady foundation, setting the tone for the song’s romantic and soulful atmosphere. His ability to balance rhythm with restraint allows the other instruments to shine while maintaining a cohesive groove. The single rose to number two on the Billboard R&B Singles Chart and to number twelve on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles Chart. It was included on the “Mr Soul” album as track number ten.

The decision to switch the recording of this album from New York to Hollywood may have been at Cooke’s suggestion. He knew the quality of the studio musicians, arrangers and engineers at RCA’s Center of the World studio and he possibly felt more comfortable recording there than in New York. His time at Specialty and Keen Records had made a strong impression on him. There was a strong team assembled for “Mr. Soul”.

Unfortunately, detailed session records specifying the exact personnel for each track are not readily available. The following musicians played on the album:

Guitarists: Clifton White, Bill Pitman, and Tommy Tedesco.

Bassists: Ray Pohlman, Clifford Hills, and Red Callender.

Drummers: Earl Palmer and Sharky Hall.

Percussionist: Ron Rich.

Pianists: Edward Beal, Ernie Freeman, Ray Johnson, and Al Pellegrini.

Organist: Nathan Griffin.

Saxophonists: Bill Green and Plas Johnson.

Trombonist: John Ewing.

Violinists: Israel Baker, Robert Barene, Leonard Malarsky, Myron Sandler, Ralph Schaeffer, Sid Sharp, Autrey McKissack, Arnold Belnick, and Jerome Reisler.

Violists: Harry Hyams and Alexander Neiman.

Cellists: Jesse Ehrlich, Irving Lipschultz, George Neikrug, and Emmet Sergeant.

French Horn Player: William Hinshaw.

The arrangements, conducted by Horace Ott and René Hall, add depth and sophistication to the album. The instrumentation complements Cooke’s emotive vocals and enhances the overall listening experience.

Dave Hassinger

Dave Hassinger, as the sound engineer on Sam Cooke’s “Mr. Soul” album, played a significant behind-the-scenes role in shaping the sonic quality of the entire album. Sam Cooke was known for his smooth, emotionally rich voice, and Hassinger’s engineering style helped capture that clarity. He had a talent for creating warm, intimate vocal recordings — essential for an artist like Cooke, whose voice carried so much nuance. On Mr. Soul, Cooke’s vocals sit right at the front of the mix, clean and resonant, which is a testament to Hassinger’s precision and sensitivity as an engineer.

Cooke demonstrates vocal sophistication over innovation, while other artists were experimenting with new sounds and breaking genre boundaries. “Mr. Soul” is more about vocal performance than musical revolution. Sam Cooke was a master craftsman of phrasing, and this album showcases that — intimate, expressive, refined. It’s less flashy but deeply nuanced, a vocal clinic wrapped in lush, clean arrangements.

Cooke was clearly aiming at both R&B and Pop audiences. The album has orchestrated arrangements and smooth backing, thanks to RCA’s polished production values, which set it apart from the grittier Soul recordings of the time (like early Motown or Stax) and shows Cooke’s crossover ambitions. His success in appealing to White as well as Black audiences was critical in breaking down musical and social barriers.

Compared to other albums released around this time, Sam Cooke’s “Mr. Soul” (1963) is a polished, emotionally rich Soul album that stands apart for its subtlety and vocal mastery. The album is a testament to Cooke’s ability to bridge genres and connect with a wide audience.

Prior to the release of the next studio album, RCA Victor released two singles that were both non-album tracks. “Bring It On Home To Me”, the first, has gone on to become one of Sam Cooke’s most enduring songs. It was originally the B-side to “Having A Party”!

The song is a clear re-working of “I Want To Go Home”, co-written by Charles Brown and Amos Milburn and recorded by them on Ace Records in 1959. Cooke’s version retains the Gospel structure of the original but replaces the lyrics turning the song into a romantic love song. The new version was recorded at RCA’s Hollywood studio on 26th April 1962, produced by Hugo & Luigi, with a studio band that included Clifton White, Tommy Tedesco and René Hall (guitars), Adolphus Alsbrook and Ray Pohlman (bass), Ernie Freeman (piano), Frank Capp (drums and percussion), and William Green (saxophone). A ten-piece string section added to the richness of the sound, and Lou Rawls sang backing vocal. René Hall arranged the music and conducted as usual. Al Schmitt was the sound engineer.

“Bring It On Home To Me” was released on 8th May. It peaked at number thirteen on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles Chart and reached number two on the Billboard R&B Singles Chart. It has become a classic, still played today and is included on the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame 500 Songs that Shaped Rock & Roll. It is simple yet unforgettable. It was very much appreciated in the UK, where it later earned a gold disc from the BPI on 30th August 2024 for over 400,000 units sold. The song was also included on the compilation album of Sam Cooke’s best Pop hits “The Best of Sam Cooke”, released in August 1962. It offered a mix of New York and Hollywood recordings. The album went on to secure gold certification in the UK on 29th December 2023, selling over one hundred thousand copies since its original release in January 1962, over half a century before, providing once again ample proof of Cooke’s lasting popularity in the UK.

The second non-album single was a version of an old traditional folk song arranged by Brook Benton. “Frankie and Johnny” was released in July 1963, a few weeks before the next album appeared. As might be expected from a Brook Benton arrangement, the song has a full orchestra backing with a built-in swing. The B-side is “Cool Train”, a Sam Cooke song, with an interesting take on big band Jazz. The quality of the recordings is excellent and Sam Cooke’s voice is, as usual on the Hollywood recordings, very much to the fore. Sales were good enough to take the single to number fourteen on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles Chart and to number four on the Billboard R&B Singles Chart. In the UK it only reached number thirty on the Official UK Pop Singles Chart.

“Night Beat” was the tenth studio album recorded by Sam Cooke. It was released by RCA Victor in August 1963. The recording sessions took place on 22nd, 23rd and 25th February 1963. These late-night sessions brought together a talented ensemble, including a young Billy Preston on organ and guitarist Barney Kessel, contributing to the album’s intimate and soulful atmosphere. “Night Beat” is one of Cooke’s most critically acclaimed works, showcasing a more intimate and Bluesy side of his music compared to his more commercial Pop and Soul recordings.

The album was produced by the renowned production duo of Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore, who were responsible for guiding its artistic direction and ensuring the cohesive sound that characterises the record. The entire album was arranged by René Hall, who also served as the conductor for the album. His role was pivotal in orchestrating the musical arrangements and leading the session musicians during the recording process. The album was once more engineered by Dave Hassinger, who managed the technical aspects of the recording sessions at RCA Victor Studios in Hollywood, California.

The musicians on the sessions were René Hall, Clifton White, Barney Kessel (guitars), Sharky Hall, Hal Blaine (drums), Ray Johnson (piano), and Billy Preston (organ). It was a deliberate decision to use a small session band, with the aim of creating a more intimate feel to the music.

Once again, the choice of songs for inclusion on the album reflects Cooke’s desire to explore a range of styles and genres. This time it’s R&B, Blues and Gospel. There are four songs written or arranged by Cooke himself, plus two from Charles Brown (one with Jesse Ervin) whose “Driftin’ Blues” was featured on the “Mr. Soul” album. Other contributors were Ella Tate, an R&B singer/ songwriter from Memphis, Willie Dixon of Chicago Blues fame, Tucker & Haywood, J. W. Alexander & Louis Jordan, Los Angeles Blues singer Johnnie Fuller, and Charles Calhoun, the songwriting name taken by R&B singer Jesse Albert Stone. The common factor in the choice of these songs seems to be their roots in early R&B and traditional Gospel music. Many of these songwriters were performers too, with links to Los Angeles.

The album’s opening song is Cooke’s interpretation of “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen”, which is a traditional African-American spiritual, dating back to the era of slavery in the United States. It’s a song of suffering, resilience, and faith. Sam Cooke’s arrangement on this album stands out for its raw, stripped-down, and deeply emotional delivery. The session musicians work extremely well together. Organist Billy Preston’s Gospel-inflected playing adds a haunting, spiritual quality to the mix. Barney Kessel on guitar contributes subtle, Bluesy riffs, accompanied by Cliff Hills on bass, laying down a steady, almost hypnotic foundation, with Hal Blaine adding sparse and subdued rhythms on the drums. The song is played at a slow tempo, accentuating the weight and depth of the lyrics. The rhythm is laid-back and contemplative, almost like a prayer or a lament. The vocal performance is very emotional with Cooke’s voice bearing a yearning and soulful quality, blending pain with hope. He uses his falsetto at moments to masterfully express vulnerability, while his deeper tones communicate resilience with powerful dynamics and phrasing. Cooke’s use of his dynamic range (soft to powerful vocals) mirrors the fluctuating emotions in the lyrics. His phrasing is deliberate, stretching syllables to enhance the song’s mournful feel. The lyrics reflect the struggles of the human spirit amid suffering. Cooke’s interpretation doesn’t just mourn — there is an undercurrent of strength, suggesting a resolve to endure despite hardships. His vocal technique on this track is almost conversational, making it feel like a personal confession or spiritual dialogue. Unlike more traditional renditions, Cooke’s version introduces a Bluesy, Soul-infused interpretation. The combination of Gospel sensibility with a Blues atmosphere is unique to this version, highlighting Cooke’s roots while also showcasing his genre-blending brilliance. The song requires subtlety and power, a balance Cooke strikes flawlessly. Cooke’s ability to convey the song’s deep emotional core without overdramatising is a testament to his maturity as an artist. Transforming a traditional spiritual into a more contemporary Soul/Blues piece demonstrates Cooke’s musical vision and innovation.

“Lost and Lookin'” comes next. It is one of the most haunting tracks on the album, characterised by its sparse instrumentation and raw, emotive delivery. The song features only a subtle, minimalistic backdrop with a slow, walking bass line and soft percussion, creating a sense of emptiness and solitude. Sam Cooke’s voice is front and centre, unembellished and stripped of studio polish. His vocals are intimate, almost as if he’s singing directly to the listener in a dimly lit room. Cooke’s delivery is restrained, with slight breaks and cracks in his voice that convey vulnerability. The way he elongates words like “lost” and “lookin’” reflects his deep sense of yearning and confusion. The track’s simplicity is its power, adding to its musical impact. The lack of instrumental complexity places full emotional weight on Cooke’s voice. The result is a song that feels deeply personal and almost painful to listen to, as it taps into universal feelings of loneliness and searching. Cooke’s voice is so exquisite, richly seductive and gorgeous from start to finish, irresistible and magnetic. He intends to pull you into the story. It is an exceptional vocal performance. Cooke’s restraint is masterful—he doesn’t overpower the song with vocal acrobatics but instead lets the quiet, aching melody breathe. The track’s beauty lies in its raw honesty, making it a standout on an album filled with soul-searching and introspective performances. The song was co-written by Cooke and J. W. Alexander, a member of the Pilgrim Travelers, who worked extensively with Sam Cooke both in the studio and for live performances while Cooke was a member of the Soul Stirrers and during his solo career as a Soul artist.

The first track on side two of the album is “Little Red Rooster”, a cover of the Blues standard written by Willie Dixon and originally recorded by Howlin’ Wolf in Chicago. Cooke’s version retains the slow-burning Blues feel of the original but he softens it with his smooth vocal delivery. The instrumentation is stripped down, featuring a small, tight combo of musicians, including Billy Preston on organ (at just 16 years old), Barney Kessel on guitar, and Hal Blaine on drums, which gives the song a late-night, intimate jam session vibe. Like most of the album’s twelve tracks, “Little Red Rooster” was recorded over a few late-night sessions in a relaxed, minimally-produced setting, focusing on emotional expression and groove rather than polished sonic expression.

Two tracks further on we find Charles Brown’s “Trouble Blues”. Cooke’s version is haunting with a simple piano backing, drums and organ. He sings it with power in a dramatic Gospel style.

Out of the album’s twelve tracks, Sam Cooke wrote three songs: “Mean Old World” (A soulful, Bluesy track that highlights Cooke’s storytelling prowess), “Laughin’ and Clownin'” (A reflective piece with a conversational and melancholy tone), and “You Gotta Move” (A Gospel-inspired track that showcases his roots and vocal dynamism).

The final track, “Shake Rattle And Roll” is fun but lacks the impact of the rest of the album.

The album is one of Cooke’s best, but it only reached number sixty-two on the Billboard 200 Albums Chart. The single “Little Red Rooster” reached number eleven on the Billboard 100 Singles Chart and number seven on the Billboard R&B Singles Chart.

In February 1964, RCA Victor released an unusual album, a collaboration between Sam Cooke, Paul Anka and Neil Sedaka. “3 Great Guys” offers four tracks by each of the artists. Hugo and Luigi produced the Sam Cooke and Paul Anka songs on album, which failed to chart. The stand-out track is Sam Cooke’s up-tempo R&B dance track “I Ain’t Gonna Cheat On You No More”.

“Ain’t That Good News” is Sam Cooke’s eleventh and final studio album before his tragic death later in 1964. The album was recorded from 28th February 1963 to the final recording sessions on 30th January 1964, at RCA Victor’s Music Center of The World in Hollywood, California. Twelve tracks were selected for this album, which was finally released in February 1964. The album represents the culmination of Cooke’s artistic evolution, blending elements of R&B, Soul, Gospel and Pop in a way that reflects his roots while demonstrating the innovations that he brought to the development of popular music.

The album was recorded during a period marked by racial tensions and a quest for equality by members of the Black communities in the United States. Cooke’s own experiences as a Black artist during this tumultuous time heavily influenced the lyrical content and emotional depth of the album.

The A-side is characterised by upbeat, feel-good tracks that reflect Cooke’s charismatic style and his roots in Gospel and R&B. Five of the six tracks on Side A are the work of Sam Cooke. They are joined by the Country standard “Tennessee Waltz”. The title track, “Ain’t That Good News”, sets a jubilant tone with its energetic brass section and lively rhythm, blending Gospel exuberance with an R&B groove. “Meet Me at Mary’s Place” balances Gospel roots with a festive, community spirit, embodying Cooke’s knack of blending personal and communal experiences, with brilliant vocal backing support from The Soul Stirrers. “Good Times” exemplifies laid-back, celebratory Soul, capturing the essence of Cooke’s smooth vocal delivery and effortless charm. “Another Saturday Night” is a quintessential R&B track with a catchy melody, reflecting themes of youthful energy and loneliness despite its upbeat tempo. Written by Cooke while touring in England, it reflects his frustration at staying in a hotel where no female guests were allowed. The lyrics express the longing of a man who has money and time but lacks companionship on a Saturday night, blending humour with a sense of longing. The recording featured a talented ensemble of musicians, including Hal Blaine on drums, John Anderson on trumpet, John Ewing on trombone, Jewell Grant on saxophone, Ray Johnson on piano, Clifton White and René Hall on guitars, and Clifford Hills on bass.

All the tracks on side A are bright and vibrant, consisting of major chords with call-and-response backing vocals reminiscent of Gospel songs. They have syncopated rhythms, typical of Soul and R&B music featuring prominent brass and string arrangements.

Side B of the album takes a more thoughtful and poignant turn, introducing deeper, more introspective themes. “A Change Is Gonna Come” is the album’s most iconic track, a Soul ballad with orchestral backing, marked by its profound sense of yearning and hope for social change. Its lush orchestration, arranged by René Hall, merges elements of Soul, Gospel, and Classical music. The sweeping strings, solemn French horn, and subtle timpani create a cinematic soundscape that mirrors the song’s hopeful yet sombre lyrics. Sam Cooke’s vocal performance is powerful and vulnerable, his rich voice conveying a deep sense of longing and determination.

“A Change Is Gonna Come” quickly became synonymous with the Civil Rights Movement. Inspired by Cooke’s personal experiences with racism, it blends personal hardship with a universal plea for justice, making it relatable to diverse audiences. Its influence transcends generations; it has been covered by artists including Aretha Franklin and Otis Redding, and referenced by Barack Obama during his presidential campaign. The song remains a timeless anthem of hope and resilience, reflecting the enduring quest for justice. It is the only track on side B written by Sam Cooke.

The remaining four tracks include one song by Irving Berlin (“Sittin’ In The Sun”) and one written by New Orleans music genius Harold Battiste (“Falling In Love”). These tracks are noteworthy for the quality of the recordings captured by sound engineer Dave Hassinger. The final track on the album is an adaptation by Sam Cooke of an old Appalachian folk song “The Riddle Song”. It was the hardest song on the album for Sam Cooke to sing. It contains the line “I gave my love a baby with no crying”. Prior to recording the eleven songs needed to complete the album (one single had already been recorded), Cooke had a break of six months following the death of his young son. Vincent Cooke was just eighteen months old when he walked into the garden at their home and fell into the family’s pool on June 17th 1963. Somehow, he managed to complete the album.

The album reached number thirty-four on the Billboard 200 Albums Chart in 1964.

Several tracks from the album were released as singles, starting with “Another Saturday Night” on 2nd April 1963, almost a year before the studio album appeared. The single peaked at number one on the Cash Box R&B Singles Chart and the Billboard Soul and R&B Singles Chart for the week ending 8th June 1963.

The second single, “(Ain’t That) Good News”, was released on 22nd January 1964. This upbeat title track showcases Cooke’s transition from Gospel to secular music, blending his Soul sound with a more Pop-oriented style. It charted at number one on the Billboard Soul and R&B Singles Chart for the week ending 14th March 1964.

The third single, “Good Times”, was backed by “Tennessee Waltz”. It was released by RCA Victor on 9th July 1964 and also performed well, peaking at number one on the Billboard Soul and R&B Singles Chart for the week ending 11th July 1964. Its rapid ascent to the top of the R&B charts underscored its immediate impact and Cooke’s significant influence in the music industry.

It is interesting to note that the album produced three number one singles on the R&B and Soul chart listings in America, yet the album itself only charted within the top thirty on the Billboard 200 Albums Chart. Singles were still dominating albums for a while yet.

There was one more non-album single issued by RCA just before Cooke died. “That’s Where It’s At”/ “Cousin of Mine” was recorded on 20th August and released on 16th September. Al Schmitt produced both tracks, with a session band that featured René Hall and Bobby Womack (guitars), June Gardner (drums), Harper Cosby (bass), John Anderson (trumpet), John “Streamline” Ewing (trombone), Jewell Grant (saxophone) and Darel Terwilliger (violin). The A-side was written by Sam Cooke and J. W. Alexander, the B-side was the work of Sam Cooke alone. The A-side reached number ninety-three on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles Chart, but as occasionally happened, the B-side proved to be more popular. “Cousin of Mine” climbed to number thirty-one on that chart and number forty on the Billboard R&B Singles Chart. Despite that lukewarm initial response from record-buyers, “That’s Where It’s At” has come to be recognised as a high-quality performance.

The final track from “Ain’t That Good News” to be released as a single was “A Change Is Gonna Come”. Amazingly, it was issued posthumously as the B-side of “Shake”, the title track of the soon-to-be-released posthumous album. Clearly, RCA promoted the A-side, which had been released to drum up expectations for the forthcoming album. “Shake” reached number seven on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles Chart and number two on the Billboard R&B Singles Chart. But the B-side was attracting attention too, with chart entries of thirty-one (Hot 100) and nine (R&B). It has slowly come to be acknowledged as one of the important songs ever written, continuing to be played and covered. In the UK the single was awarded gold certification by the BPI. In the UK the single was awarded gold certification by the BPI on 3rd November 2023 for sales of over 400,000 copies, following a strong marketing campaign by Universal, who had acquired the rights to the catalogue. As a result of that campaign, the single entered the Official UK Pop Singles Chart on 24th May 2023, climbing to number thirty-five.

In retrospect, “Ain’t That Good News” stands not only as a testament to Sam Cooke’s unparalleled artistry but also as a profound reflection of his journey through music and life. The album’s blend of Soul, Gospel, R&B, and Pop encapsulates Cooke’s versatility and creative genius, while tracks like “A Change Is Gonna Come” continue to resonate as powerful anthems of hope and resilience. Released during a pivotal era in American history, the album’s emotional depth and social consciousness affirm Cooke’s enduring legacy as both a musical innovator and a voice of change. Decades later, his songs continue to inspire new generations, reminding us of the timeless connection between music and the human spirit.

During his career, Sam Cooke achieved only one number one single on the Billboard Hot 100 Pop Singles Chart with “You Send Me” in 1957, released by Keen Records, which marked his breakthrough into mainstream success.

On the Billboard R&B Singles Chart and the Cash Box R&B Chart, he secured a total of four number one singles. These were all recorded with RCA Records and all the singles were recorded in Los Angeles. They were: “Twistin’ the Night Away”, “Good Times”, “(Ain’t That) Good News”, and “Another Saturday Night”. These tracks (and many others!) exemplify Cooke’s mastery of Rhythm and Blues and highlight his commercial and artistic peak in the early 1960s. They also reflect his lasting legacy as one of the founding voices of Soul music. He has had and continues to have a significant influence on popular music and on Gospel music too.