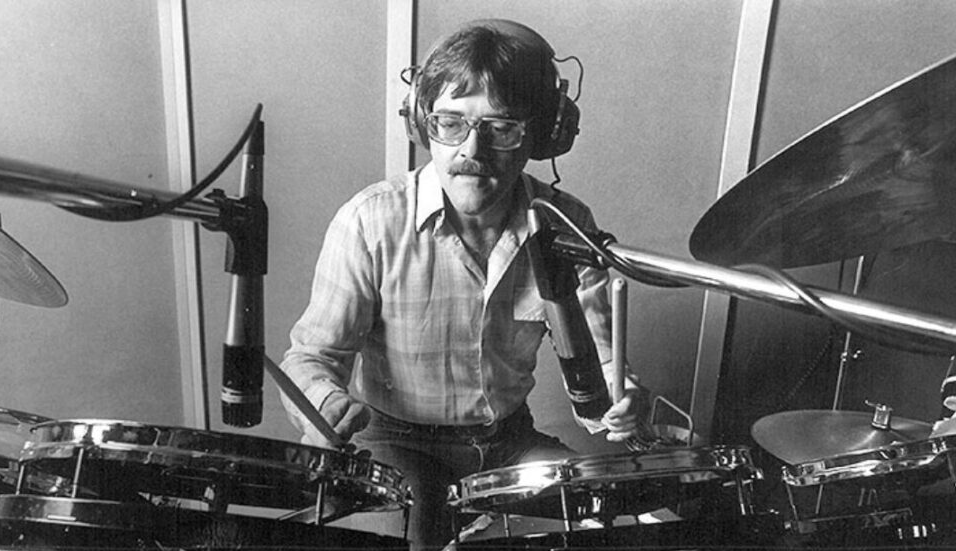

Roger Hawkins was born in 1945 in Mishawaka, Indiana. He grew up in a town called Greenhill in Alabama, around twenty miles from Muscle Shoals. At the age of thirteen, he started to play drums and soon joined the Del-Rays. They began recording at FAME Studios, where he met Rick Hall, who invited him to join the second session band at FAME. He also found work at Quin Ivy’s Norala Studio, where one of his first sessions was Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman”. What a great start to his career as a session musician!

Roger Hawkins

In any band, the drummer is the anchor. The beat they set is the heartbeat of the music. All the best studios had a great drummer, and FAME was no exception. Hawkins was a master of his art, despite not being able to read music. None of the band could! As Hawkins has explained, his skill was listening to a song and finding a drumbeat that enhanced it.

He listened and stored musical ideas, ready to use them when the right song came along:

“I was a better listener than player and I think the other guys were too”. (My Drum Lessons, Sunday, April 30th, 2017). “They loved music and they had catalogs of music in their brains, just like I had a catalog of stuff where I could pull out certain things and make it work with newer stuff.” (Roger Hawkins speaking with Daniel Kreps, Rolling Stone magazine, May 2021).

There are many recordings that demonstrate his skills and his originality. For “I’ll Take You There” he developed an intricate cymbal pattern with a soft edge, accompanied by David Hood on bass, who provided a funky bottom line. His solid back beats transformed such songs as “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” or “Respect Yourself”. The intro of “Respect Yourself” has drumbeats that move from soft to hard and back to soft, a reggae pattern influenced by sounds originally developed on the island of Jamaica.

The biggest influence on Hawkin’s playing style was much nearer home: Al Jackson Jr. in Memphis. Hawkins has described the impact of hearing “Green Onions” for the first time and rushing out to buy the record. The music recorded at Stax Records provided him with some wonderful examples to follow.

However, Hawkins didn’t just copy. He was also an experimenter. In an interview with Jeff Porter of Modern Drummer, Hawkins explained how he got the sound Paul Simon wanted for “Kodachrome”: “I call it a loping feel. That was the drums, but that didn’t get the feel enough… And I sure as hell couldn’t play it on the bass drum. So I got an old two-inch tape box, like the big reels used to come in. I put some newspaper in the box and played the pattern on it with hard vibes mallets. I listened back to it, though, and it wasn’t quite cutting through. So I kept changing the packing in the box until it came through well. That’s where the loping feel comes from. I don’t know if that drum part would have sounded that good without it”.

Roger Hawkins was not a flamboyant player in the mould of some Jazz or Rock drummers of the 1960s and 1970s. Instead, his genius lay in restraint, groove, and precision. He mastered the art of playing for the song, rather than for show, and in doing so he became one of the most distinctive drummers in popular music. Hawkins’ style was defined by his ability to sit deep “in the pocket”. He rarely overplayed, preferring simple, uncluttered patterns that gave singers and other musicians space to shine. His drumming on Wilson Pickett’s “Mustang Sally” is a classic example: steady hi-hat, crisp snare, and a driving backbeat that never falters. There are no unnecessary fills, no attempt to dominate. The groove itself carries the song, and Hawkins’ feel makes it swing without rushing. Hawkins also had a gift for subtle syncopation, introducing slight rhythmic shifts that added tension and release without disturbing the groove. On Aretha Franklin’s “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)”, his drumming is almost conversational, punctuating her vocal lines with carefully placed accents. It feels instinctive, as though Hawkins was breathing with the singer, shaping the track around her phrasing.

Unlike many drummers who relied on sheer power or flamboyant flourishes, Hawkins’ precision was never rigid. His playing always retained a human looseness, a sense of natural swing. On The Staple Singers’ “I’ll Take You There”, his relaxed groove underpins the trance-like bassline. The drums feel effortless, almost casual, yet they are immovable, an anchor around which the song revolves. His snare, especially, carried a crisp, popping quality that cut through the mix without ever sounding harsh.

Hawkins could adapt his style seamlessly across genres. With Paul Simon’s “Kodachrome”, he shifted to a more upbeat, Pop-Rock feel, providing brightness and bounce. On Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock and Roll”, he delivered straight-ahead drive, tight and punchy. Yet in every case, his drumming remained invisible in the best sense: listeners felt the song’s pulse without being distracted by technical showmanship. Roger Hawkins’ signature was not flashy technique but emotional precision. He played with an acute awareness of space, time, and feel, shaping the atmosphere of a song with a few well-placed beats. His drumming was the glue of the Muscle Shoals sound—never overstated, always reliable, and unfailingly musical. Where other drummers might have sought to impress, Hawkins chose to serve, and in that service, he left an indelible mark on some of the most iconic recordings of the 20th century.